Even today, with the overwhelming success of Spring and the rise of smaller, simpler approaches to building applications (in contrast to the heavyweight EJB 2.0 approach), many people still have trouble wrapping their heads around Inversion of Control.

Really understanding IoC is a new step for many developers. If you can remember back to when you made the transition from procedural programming (in C, or BASIC) to object oriented programming, you might remember the point where you "got it". The point where it made sense to have methods on objects, and data inside objects.

Inversion of Control builds upon those ideas. The goal is to make code more robust (that is, with fewer errors), more reusable and much easier to test.

Prior to IoC approaches, most developers were used to a more monolithic design, with a few core objects and a main() method somewhere that starts the ball rolling. main() instantiates the first couple of classes, and those classes end up instantiating and using all the other classes in the system.

That's an unmanaged system. Most desktop applications are unmanaged, so it's a very familiar pattern, and easy to get your head around.

By contrast, web applications are a managed environment. You don't write a main(), you don't control startup. You configure the Servlet API to tell it about your servlet classes to be instantiated, and their life cycle is totally controlled by the servlet container.

Inversion of Control is just a more general application of this approach. The container is ultimately responsible for instantiating and configuring the objects you tell it about, and running their entire life cycle of those objects.

Web applications are more complicated to write than monolithic applications, largely because of multithreading. Your code will be servicing many different users simultaneously across many different threads. This tends to complicate the code you write, since some fundamental aspects of object oriented development get called into question: in particular, the use of internal state (values stored inside instance variables), since in a multithreaded environment, that's no longer the safe place it is in traditional development. Shared objects plus internal state plus multiple threads equals an broken, unpredictable application.

Frameworks such as Tapestry – both the IoC container, and the web framework itself – exist to help.

When thinking in terms of IoC, small is beautiful. What does that mean? It means small classes and small methods are easier to code than large ones. At one extreme, we have servlets circa 1997 (and Visual Basic before that) with methods a thousand lines long, and no distinction between business logic and view logic. Everything mixed together into an untestable jumble.

At the other extreme is IoC: small objects, each with a specific purpose, collaborating with other small objects.

Using unit tests, in collaboration with tools such as EasyMock, you can have a code base that is easy to maintain, easy to extend, and easy to test. And by factoring out a lot of plumbing code, your code base will not only be easier to work with, it will be smaller.

Living on the Frontier

Coding applications the traditional way is like being a homesteader on the American frontier in the 1800's. You're responsible for every aspect of your house: every board, every nail, every stick of furniture is something you personally created. There is a great comfort in total self reliance. Even if your house is small, the windows are a bit drafty or the floorboards creak a little, you know exactly why things are not-quite perfect.

Flash forward to modern cities or modern suburbia and it's a whole different story. Houses are built to specification from design plans, made from common materials, by many specializing tradespeople. Construction codes dictate how plumbing, wiring and framing should be performed. A home-owner may not even know how to drive a nail, but can still take comfort in draft-free windows, solid floors and working plumbing.

To extend the metaphor, a house in a town is not alone and self-reliant the way a frontier house is. The town house is situated on a street, in a neighborhood, within a town. The town provides services (utilities, police, fire control, streets and sewers) to houses in a uniform way. Each house just needs to connect up to those services.

The World of the Container

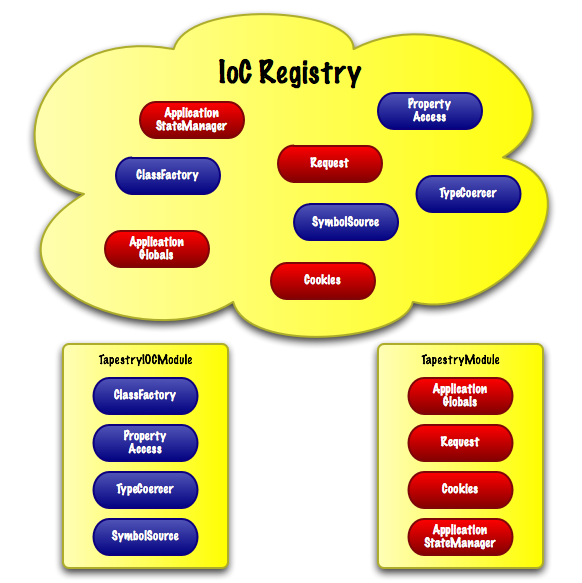

So the IoC container is the "town" and in the world of the IoC container, everything has a name, a place, and a relationship to everything else in the container. Tapestry calls this world "The Registry".

Here we're seeing a few services from the built-in Tapestry IoC module, and a few of the services from the Tapestry web framework module. In fact, there are over 100 services, all interrelated, in the Registry ... and that's before you add your own to the mix. The IoC Registry treats all the services uniformly, regardless of whether they are part of Tapestry, or part of your application, or part of an add-on library.

Tapestry IoC's job is to make all of these services available to each other, and to the outside world. The outside world could be a standalone application, or it could be an application built on top of the Tapestry web framework.

Service Life Cycle

Tapestry services are lazy, which means they are not fully instantiated until they are absolutely needed. Often, what looks like a service is really a proxy object ... the first time any method of the proxy is invoked, the actual service is instantiated and initialized (Tapestry uses the term realized for this process). Of course, this is all absolutely thread-safe.

Initially a service is defined, meaning some module has defined the service. Later, the service will be virtual, meaning a proxy has been created. This occurs most often because some other service depends on it, but hasn't gotten around to invoking methods on it. Finally, a service that is ready to use is realized. What's nice is that your code neither knows nor cares about the life cycle of the service, because of the magic of the proxy.

In fact, when a Tapestry web application starts up, before it services its first request, only about 20% of the services have been realized; the remainder are defined or virtual.

Class vs. Service

A Tapestry service is more than just a class. First of all, it is a combination of an interface that defines the operations of the service, and an implementation class that implements the interface.

Why this extra division? Having a service interface is what lets Tapestry create proxies and perform other operations. It's also a very good practice to code to an interface, rather than a specific implementation. You'll often be surprised at the kinds of things you can accomplish by substituting one implementation for another.

Tapestry is also very aware that a service will have dependencies on other services. It may also have other needs ... for example, in Tapestry IoC, the container provides services with access to Loggers.

Tapestry IoC also has support for other configuration that may be provided to services when they are realized.

Dependency Injection

Main Article: Injection

Related Articles

Inversion of Control refers to the fact that the container, here Tapestry IoC's Registry, instantiates your classes. It decides on when the classes get instantiated.

Dependency Injection is a key part of realization: this is how a service is provided with the other services it needs to operate. For example, a Data Access Object service may be injected with a ConnectionPool service.

In Tapestry, injection occurs through constructors, through parameters to service builder methods, or through direct injection into fields. Tapestry prefers constructor injection, as this emphasizes that dependencies should be stored in final variables. This is the best approach towards ensuring thread safety.

In any case, injection "just happens". Tapestry finds the constructor of your class and analyzes the parameters to determine what to pass in. In some cases, it uses just the parameter type to find a match, in other cases, annotations on the parameters may also be used. It also scans through the fields of your service implementation class to identify which should have injected values written into them.

Why can't I just use new?

That's a common question. All these concepts seem alien at first. What's wrong with new?

The problem with new is that it rigidly connects one implementation to another implementation. Let's follow a progression that reflects how a lot of projects get written. It will show that in the real world, new is not as simple as it first seems.

This example is built around some real-world work that involves a Java Messaging Service queue, part of an application performance monitoring subsystem for a large application. Code inside each server collects performance data of various types and sends it, via a shared JMS queue, to a central server for collection and reporting.

This code is for a metric that periodically counts the number of rows in a key database table. Other implementations of MetricProducer will be responsible for measuring CPU utilization, available disk space, number of requests per second, and so forth.

public class TableMetricProducer implements MetricProducer

{

. . .

public void execute()

{

int rowCount = . . .;

Metric metric = new Metric("app/clients", System.currentTimeMillis(), rowCount);

new QueueWriter().sendMetric(metric);

}

}

We've omitted some of the details (this code will need a database URL or a connection pool to operate), so as to focus on the one method and it's relationship to the QueueWriter class.

Obviously, this code has a problem ... we're creating a new QueueWriter for each metric we write into the queue, and the QueueWriter presumably is going to open the JMS queue fresh each time, an expensive operation. Thus:

public class TableMetricProducer implements MetricProducer

{

. . .

private final QueueWriter queueWriter = new QueueWriter();

public void execute()

{

int rowCount = . . .;

Metric metric = new Metric("app/clients", System.currentTimeMillis(), rowCount);

queueWriter.sendMetric(metric);

}That's better. It's not perfect ... a proper system might know when the application was being shutdown and would shut down the JMS Connection inside the QueueWriter as well.

Here's a more immediate problem: JMS connections are really meant to be shared, and we'll have lots of little classes collecting different metrics. So we need to make the QueueWriter shareable:

private final QueueWriter queueWriter = QueueWriter.getInstance();... and inside class QueueWriter:

public class QueueWriter

{

private static QueueWriter instance;

private QueueWriter()

{

...

}

public static getInstance()

{

if (instance == null)

{

instance = new QueueWriter();

}

return instance;

}

}

Much better! Now all the metric producers running inside all the threads can share a single QueueWriter. Oh wait ...

public synchronized static getInstance()

{

if (instance == null)

{

instance = new QueueWriter();

}

return instance;

}

Is that necessary? Yes. Will the code work without it? Yes – 99.9% of the time. In fact, this is a very common error in systems that manually code a lot of these construction patterns: forgetting to properly synchronize access. These things often work in development and testing, but fail (with infuriating infrequency) in production, as it takes two or more threads running simultaneously to reveal the coding error.

Wow, we're a long way from a simple new already, and we're talking about just one service. But let's detour into testing.

How would you test TableMetricProducer? One way would be to let it run and try to find the message or messages it writes in the queue, but that seems fraught with difficulties. It's more of an integration test, and is certainly something that you'd want to execute at some stage of your development, but not as part of a quick-running unit test suite.

Instead, let's split QueueWriter in two: a QueueWriter interface, and a QueueWriterImpl implementation class. This will allow us to run TableMetricProducer against a mock implementation of QueueWriter, rather than the real thing. This is one of the immediate benefits of coding to an interface rather than coding to an implementation.

We'll need to change TableMetricProducer to take the QueueWriter as a constructor parameter.

public class TableMetricProducer implements MetricProducer

{

private final QueueWriter queueWriter;

/**

* The normal constructor.

*

*/

public TableMetricProducer(. . .)

{

this(QueueWriterImpl.getInstance(), . . .);

}

/**

* Constructor used for testing.

*

*/

TableMetricProducer(QueueWriter queueWriter, . . .)

{

queueWriter = queueWriter;

. . .

}

public void execute()

{

int rowCount = . . .;

Metric metric = new Metric("app/clients", System.currentTimeMillis(), rowCount);

queueWriter.sendMetric(metric);

}

}

This still isn't ideal, as we still have an explicit linkage between TableMetricProducer and QueueWriterImpl.

What we're seeing here is that there are multple concerns inside the little bit of code in this example. TableMetricProducer has an unwanted construction concern about which implementation of QueueWriter to instantiate (this shows up as two constructors, rather than just one). QueueWriterImpl has an additional life cycle concern, in terms of managing the singleton.

These extra concerns, combined with the use of static variables and methods, are a bad design smell. It's not yet very stinky, because this example is so small, but these problems tend to multiply as an application grows larger and more complex, especially as services start to truly collaborate in earnest.

For comparison, lets see what the Tapestry IoC implementation would look like:

public class MonitorModule

{

public static void bind(ServiceBinder binder)

{

binder.bind(QueueWriter.class, QueueWriterImpl.class);

binder.bind(MetricScheduler.class, MetricSchedulerImpl.class);

}

public void contributeMetricScheduler(Configuration<MetricProducer> configuration, QueueWriter queueWriter, . . .)

{

configuration.add(new TableMetricProducer(queueWriter, . . .))

}

}

Again, we've omitted a few details related to the database the TableMetricProducer will point at (in fact, Tapestry IoC provides a lot of support for configuration of this type as well, which is yet another concern).

The MonitorModule class is a Tapestry IoC module: a class that defines and configures services.

The bind() method is the principle way that services are made known to the Registry: here we're binding a service interface to a service implementation. QueueWriter we've discussed already, and MetricScheduler is a service that is responsible for determining when MetricProducer instances run.

The contributeMetricScheduler() method allows the module to contribute into the MetricProducer service's configuration. More testability: the MetricProducer isn't tied to a pre-set list of producers, instead it will have a Collection<MetricProducer> injected into its constructor. Thus, when we're coding the MetricProducerImpl class, we can test it against mock implementations of MetricProducer.

The QueueWriter service is injected into the contributeMetricScheduler() method. Since there's only one QueueWriter service, Tapestry IoC is able to "find" the correct service based entirely on type. If, eventually, there's more than one QueueWriter service (perhaps pointing at different JMS queues), you would use an annotation on the parameter to help Tapestry connect the parameter to the appropriate service.

Presumably, there would be a couple of other parameters to the contributeMetricScheduler() method, to inject in a database URL or connection pool (that would, in turn, be passed to TableMetricProducer).

A new TableMetricProducer instance is created and contributed in. We could contribute as many producers as we like here. Other modules could also define a contributeMetricScheduler() method and contribute their own MetricProducer instances.

Meanwhile, the QueueWriterImpl class no longer needs the instance variable or getInstance() method, and the TableMetricProducer only needs a single constructor.

Advantages of IoC: Summary

It would be ludicrous for us to claim that applications built without an IoC container are doomed to failure. There is overwhelming evidence that applications have been built without containers and have been perfectly successful.

What we are saying is that IoC techniques and discipline will lead to applications that are:

- More testable – smaller, simpler classes; coding to interfaces allows use of mock implementations

- More robust – smaller, simpler classes; use of final variables; thread safety baked in

- More scalable – thread safety baked in

- Easier to maintain – less code, simpler classes

- Easier to extend – new features are often additions (new services, new contributions) rather than changes to existing classes

What we're saying is that an IoC container allows you to work faster and smarter.

Many of these traits work together; for example, a more testable application is inherently more robust. Having a test suite makes it easier to maintain and extend your code, because its much easier to see if new features break existing ones. Simpler code plus tests also lowers the cost of entry for new developers coming on board, which allows for more developers to work efficiently on the same code base. The clean separation between interface and implementation also allows multiple developers to work on different aspects of the same code base with a lowered risk of interference and conflict.

By contrast, traditional applications, which we term monolithic applications, are often very difficult to test, because there are fewer classes, and each class has multiple concerns. A lack of tests makes it more difficult to add new features without breaking existing features. Further, the monolithic approach more often leads to implementations being linked to other implementations, yet another hurdle standing in the way of testing.

Let's end with a metaphor.

Over a decade ago, when Java first came on the scene, it was the first mainstream language to support garbage collection. This was very controversial: the garbage collector was seen as unnecessary, and a waste of resources. Among C and C++ developers, the attitude was "Why do I need a garbage collector? If I call malloc() I can call free()."

But now, most developers would never want to go back to a non-garbage collected environment. Having the GC around makes it much easier to code in a way we find natural: many small related objects working together. It turns out that knowing when to call free() is more difficult than it sounds. The Objective-C language tried to solve this with retain counts on objects and that still lead to memory leaks when it was applied to object graphs rather than object trees.

Roll the clock forward a decade and the common consensus has shifted considerably. Objective-C 2.0 features true garbage collection and GC libraries are available for C and C++. All scripting languages, including Ruby and Python, feature garbage collection as well. A new language without garbage collection is now considered an anomaly.

The point is, the life cycle of objects turns out to be far more complicated than it looks at first glance. We've come to accept that our own applications lack the ability to police their objects as they are no longer needed (they literally lack the ability to determine when an object is no longer needed) and the garbage collector, a kind of higher authority, takes over that job very effectively. The end result? Less code and fewer bugs. And a careful study shows that the Java memory allocator and garbage collector (the two are quite intimately tied together) is actually more efficient than malloc() and free().

So we've come to accept that the death concern is better handled outside of our own code. The use of Inversion of Control is simply the flip side of that: the life cycle and construction concerns are also better handled by an outside authority as well: the IoC container. These concerns govern when a service is realized and how its dependencies and configuration are injected. As with the garbage collector, ceding these chores to the container results in less code and fewer bugs, and lets you concentrate on the things that should matter to you: your business logic, your application – and not a whole bunch of boilerplate plumbing!