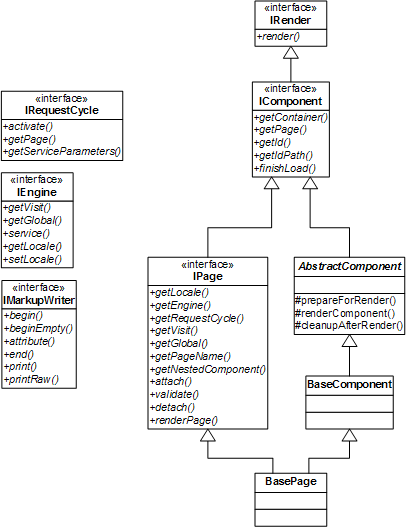

Tapestry is a component based web application framework; components, objects which implement the IComponent interface, are the fundamental building blocks of Tapestry. Additional objects, such as the the engine, IMarkupWriter and the request cycle are infrastructure. The following figure identifies the core Tapestry classes and interfaces.

Tapestry components can be simple or complex. They can be specific to a single application or completely generic. They can be part of an application, or they can be packaged into a component library .

All the techniques used with pages work with components as well ... pages are a specialized kind of Tapestry component. This includes specified properties (including persistent properties) and listener method s.

Components fit into the overall page rendering process because they implement the

IRender

interface. Components that inherit from

BaseComponent

will use an HTML template. Components that inherit from

AbstractComponent

will render output in Java code, by implementing method

renderComponent()

.

The components provided with the framework are not special in any way: they don't have access to any special APIs or perform any special down-casts. Anything a framework component can do, can be done by your own components.

Every component has a component specification, a file ending with a .jwc extension, whose root element is <component-specification> .

Each component's specification defines the basic characteristics of the component:

Tapestry searches for components in the following places:

renderComponent()

method. This method is invoked when the component's container (typically, but

not always, a page) invokes its own

renderBody()

method.

protected void renderComponent(IMarkupWriter writer, IRequestCycle cycle) { . . . }

print()

methods that output text (the method is overloaded for different types). It also

contains

printRaw()

methods -- the difference being that

print()

uses a filter to convert certain characters into HTML entities.

IMarkupWriter

also includes methods to simplify creating markup style output: that is,

elements with attributes.

For example, to create a <a> link:

public void renderComponent(IMarkupWriter writer, IRequestCycle cycle) { . . . writer.begin("a"); writer.attribute("url", url); writer.attribute("class", styleClass); renderBody(writer, cycle); writer.end(); // close the <a> }

The

begin()

method renders an open tag (the <a>, in this case). The

end()

method renders the corresponding </a>. As you can see, writing attributes

into the tag is equally simple.

The call to

renderBody()

is used to render

this

component's body. A component doesn't have to render its body; the standard

Image

component doesn't render its body (and its component specification indicates

that it discards its body). The

If

component decides whether or not to render its body, and the

For

component may render its body multiple times.

A component that allows informal parameters can render those as well:

writer.beginEmpty("img");

writer.attribute("src", imageURL);

renderInformalParameters(writer, cycle);

This example will add any informal parameters for the component as additional

attributes within the <img> element. These informal parameters can be

specified in the page's HTML template, or within the

<component>

tag of the page's specification. Note the use of the

beginEmpty()

method, for creating a start tag that is not balanced with an end tag (or a call

to the

end()

method).

A Tapestry page consists of a number of components. These components communicate with, and coordinate with, the page (and each other) via parameters .

A formal component parameter has a unique name, and may be optional or required. Optional parameters may have a default value. The <parameter> component specification element is used to define formal component parameters.

In a traditional desktop application, components have properties . A controller may set the properties of a component, but that's it: properties are write-and-forget.

The Tapestry model is a little more complex. A component's parameters are bound to properties of the enclosing page (or component). The component is allowed to read its parameter, to access the page property the parameter is bound to. A component may also update its parameter, to force a change to the bound page property. In fact, behind the scenes, each component parameter has a binding object, an instance of type IBinding , that is used to read or update the property.

The vast majority of components simply read their parameters. Updating parameters is more rare; the most common components that update their parameters are form element components such as TextField or Checkbox .

Because bindings are often in the form of OGNL expressions, the property bound to a component parameter may not directly be a property of the page ... using a property sequence allows great flexibility.

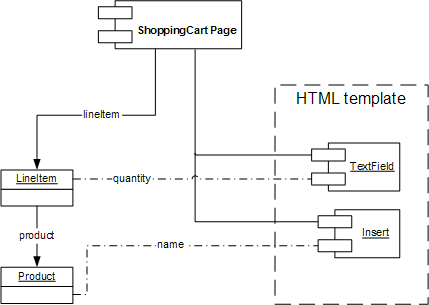

Using OGNL , the TextField component's value parameter is bound to the LineItem's quantity property, using the OGNL expression lineItem.quantity, and the Insert component's value parameter is bound to the Product's name property using the OGNL expression lineItem.product.name.

When using localized messages (the message: prefix) or literal strings (no prefix), there is still a binding object, just a binding of a different type. Not all bindings are writable. OGNL expressions may be writeable, if the expression identifies a property that is itself writeable. Most other types of bindings are read only.

To access a component parameter inside Java code is simply a matter of defining an accessor method. For example, if your component has a title parameter, then you define a getTitle() accessor method:

public abstract String getTitle(); public void renderComponent(IMarkupWriter writer, IRequestCycle cycle) { writer.begin("a"); writer.attribute("href", . . .); writer.attribute("title", getTitle()); . . . }

When your code invokes getTitle(), the binding for the title parameter will be used to obtain a value, which is returned. Likewise, invoking setTitle() will use the binding for the title parameter to update the bound value.

Note:If you are upgrading from Tapestry 3.0, you may be wondering "how do I specify parameter direction now?". Parameter direction was a hint you would provide to Tapestry that would tell Tapestry when it was appropriate to copy values into, or out of, component parameter properties. This is no longer necessary in Tapestry 4.0 -- the runtime code generation for parameter properties is much more sophisticated. All parameters are now similar to Tapestry 3.0's auto direction, but much smarter. Tapestry 3.0 auto parameters were only useable with required parameters and were inefficient. In Tapestry 4.0, parameter values are cached such that the OGNL expression does not have to be evaluated every time the parameter is accessed and things still work properly for optional parameters.

There are two ways to set default values for parameters. You may provide a default-value attribute in the <parameter> element. This is, effectively, a binding to use if no binding is provided.

<parameter name="title" default-value="literal:Link to current thread"/>

Remember that outside of the template, all binding reference s, including the default-value attribute, default to OGNL expressions. Therefore, it is necessary to prefix the default value with the literal: prefix to ensure that Tapestry doesn't treat it as an expression.

What's nice is that the default value doesn't have to be a simple string; it can be a computed OGNL expression, or a reference to a localized message:

<parameter name="title" default-value="message:link-title"/>

link-title=Link to current thread

The second approach to defining default values for parameters is to set the parameter's property from the component's finishLoad() method.

public abstract void setTitle(String title);

protected void finishLoad()

{

super.finishLoad();

setTitle("Link to current thread");

}

Even with parameter defaults, there are times when you want to behave differently depending on whether a parameter is bound or not bound. The method isParameterBound() exists for those cases:

public abstract String getTitle(); public void renderComponent(IMarkupWriter writer, IRequestCycle cycle) { writer.begin("a"); writer.attribute("href", . . .); if (isParameterBound("title")) writer.attribute("title", getTitle()); . . . }

Using isParameterBound() is most useful with parameters whose type is a primitive type. In the previous example, we could simply invoke getTitle() and see if the result is null. For, say, an int property, we would need a way to distinguish between 0 and no value provided ... that's what isParameterBound() is for.

Note that you always pass the name of the parameter to the isParameterBound() method, even when you've used the property attribute of the <parameter> element to use a different property name:

<parameter name="title" property="titleParameter"/>

public abstract String getTitleParameter(); public void renderComponent(IMarkupWriter writer, IRequestCycle cycle) { writer.begin("a"); writer.attribute("href", . . .); if (isParameterBound("title")) writer.attribute("title", getTitleParameter()); . . . }

When Tapestry enhances a class to add a component property, it (by default) caches the value of the binding for the duration of the component's render. That is, while a component is rendering, it will (at most) use the parameter's binding once, and store the result internally, clearing the cached value as the component finishes rendering. The parameter property can be accessed when the component is not rendering (an important improvement from Tapestry 3.0), the result simply is not cached (each access to the property when the component is not rendering is another access via the binding object).

This caching behavior is not always desired; in some cases, the component operates best with caching disabled. The <parameter> element's cache parameter can be set to "false" to defeat this caching.

However, for the majority of binding types (most types except for "ognl"), the value obtained is invariant ... it will always be the same value. Values obtained from invariant bindings are always cached indefinately (not just for the component's render). In other words, literal string values, localized messages and so forth are accessed via the binding just once. This is great for efficiency ; after "warming up", a Tapestry page will render faster the second time through, because so many component parameters are invariant and already in place inside component properties.

On the other hand, informal parameters are not cached at all; the values for such parameters are always re-obtained from the binding object on each use.

Note:When using 3.0 DTDs with Tapestry 4.0, parameters with direction "auto" are not cached . Other direction types (or no direction specified) are cached. There is no real support for direction "custom" in 4.0 ... all parameters will be realized as parameter properties.

Tapestry has a very advanced concept of a component library . A component library contains both Tapestry components and Tapestry pages (not to mention engine services).

Before a component library may be used, it must be listed in the application specification. Often, an application specification is only needed so that it may list the libraries used by the application. Libraries are identified using the <library> element.

The <library> element provides an id for the library, which is used to reference components (and pages) within the library. It also provides a path to the library's specification. This is a complete path for a .library file on the classpath. For example:

<application name="Example Application">

<library id="contrib" specification-path="/org/apache/tapestry/contrib/Contrib.library"/>

</application>In this example, Contrib.library defines a set of components, and those component can be accessed using contrib: as a prefix. In an HTML template, this might appear as:

<span jwcid="palette@contrib:Palette" . . . />

This example defines a component with id

palette

. The component will be an instance of the Palette component, supplied

within the contrib component library. If an application uses multiple

libraries, they will each have their own prefix. Unlike JSPs and JSP tag

libraries, the prefix is set once, in the application specification, and is

used consistently in all HTML templates and specifications within the

application.

The same syntax may be used in page and component specifications:

<component id="palette" type="contrib:Palette"> . . . </component>

Previously , we described the search path for components and pages within the application. The rules are somewhat different for components and pages within a library.

Tapestry searches for library component specifications in the following places:

<asset name="logo" path="images/logo_200.png"/>

<component id="image" type="Image">

<binding name="image" value="asset:logo"/>

</component>

In this case, if the component is packaged as /com/example/mylibrary/MyComponent.jwc, then the asset will be /com/examples/mylibrary/images/logo_200.png. Further, the asset path will be localized.

All assets (classpath, context or external) are converted into instances of IAsset and treated identically by components (such as Image ). As in this example, relative paths are allowed: they are interpreted relative to the specification (page or component) they appear in.

The Tapestry framework will ensure that an asset will be converted to a valid URL that may be referenced from a client web browser ... even though the actual service is inside a JAR or otherwise on the classpath, not normally referenceable from the client browser.

The default behavior is to serve up the localized resource using the asset service. In effect, the framework will read the contents of the asset and pipe that binary content down to the client web browser.

An alternate behavior is to have the framework copy the asset to a fixed directory. This directory should be mapped to a known web folder; that is, have a URL that can be referenced from a client web browser. In this way, the web server can more efficiently serve up the asset, as a static resource (that just happens to be copied into place in a just-in-time manner).

This behavior is controlled by a pair of configuration properties : org.apache.tapestry.asset.dir and org.apache.tapestry.asset.URL.

A library specification is a file with a .library extension. Library specifications use a root element of <library-specification> , which supports a subset of the attributes allowed within an <application> element (but allowing the same nested elements). Often, the library specification is an empty placeholder, used to an establish a search location for page and component specifications:

<!DOCTYPE library-specification PUBLIC "-//Apache Software Foundation//Tapestry Specification 3.0//EN" "http://jakarta.apache.org/tapestry/dtd/Tapestry_3_0.dtd"> <library-specification/>

It is allowed that components in one library be constructed using components provided by another library. The referencing library's specification may contain <library> elements that identify some other library.

Tapestry organizes components and pages (but not engine services) into namespaces . Namespaces are closely related to, but not exactly the same as, the library prefix established using the <library> element in an application or library specification.

Every Tapestry application consists of a default namespace, the application namespace. This is the namespace used when referencing a page or component without a prefix. When a page or component can't be resolved within the application namespace, the framework namespace is searched. Only if the component (or page) is not part of the framework namespace does an error result.

In fact, it is possible to override both pages and components provided by the framework. This is frequently used to change the look and feel of the default StateSession or Exception page. In theory, it is even possible to override fundamental components such as Insert or For !

Every component provides a namespace property that defines the namespace (an instance of INamespace ) that the component belongs to.

You rarely need to be concerned with namespaces, however. The rare exception is when a page from a library wishes to make use of the PageLink or ExternalLink components to create a link to another page within the same namespace. This is accomplished (in the source page's HTML template) as:

<a href="#" jwcid="@PageLink" page="OtherPage" namespace="ognl:namespace"> ... </a>